Overview

In July of 2025, my brother Cade and I spent a weekend cranking out Perry’s Powered Power-Ups, a Sokoban-inspired puzzle demo for the Kenney Game Jam, inspired by the theme “Power” (we were subtle, I know).

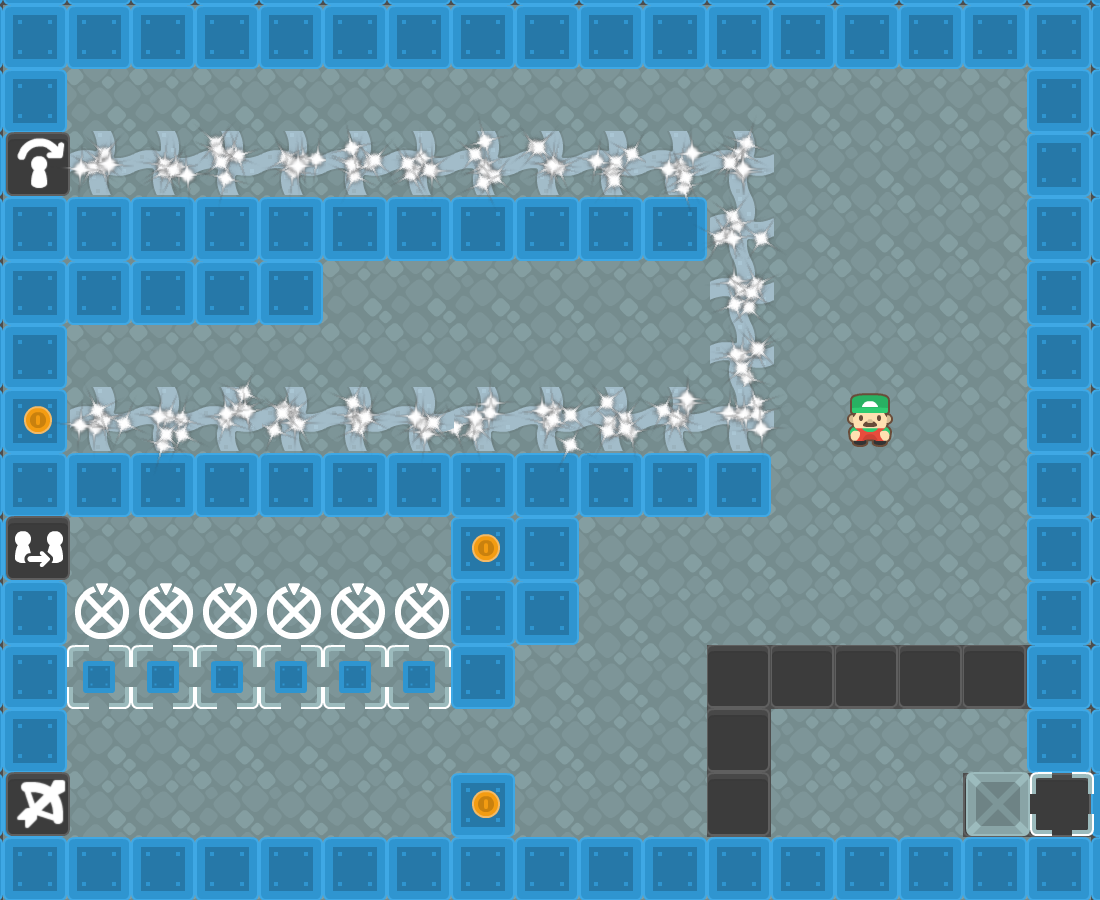

The objective is to move around the grid in each room, plugging in power sockets to charge your power-ups! Perry can gain abilities like jump, hopping over the placed cable to reach previously-blocked squares; dash, speeding over holes in the factory; and shoot, knocking down targets to unlock barricades.

Thanks to the second rule of the Jam, requiring players to use only the incredible assets provided by Kenney, our game had a colorful, cartoonish aesthetic to it. I was satisfied with how the game came out and what we could accomplish in just 48 hours.

During the Jam

The first thing I did when the Jam started was to work for a day. Not ideal, but since it started a 9am PST on Friday, I didn’t have much choice. This was definitely a factor in running short on time, but there’s only so much more we really could have gotten accomplished.

Once the workday wrapped up, Cade and I met to continue brainstorming. We had chatted the night before about what game engine we would use and what kind of game we planned on making. Even though we didn’t know the theme, it was useful to have a sense for what kind of mechanics we’d use.

Now armed with the theme, we had three initial ideas:

- a puzzle game where the player restores light (power) to a town

- a debate / mystery style game, like Ace Attorney, where you exercise your power over people is important

- a multi-mechanic game, similar to Split Fiction, where we restore power by completing a few different minigames that coalesces at the end

We ended up deciding on the puzzle game due to scope concerns and our ability to come up with content. I think it was the right decision, considering how much we weren’t able to accomplish. And we still did so much!

Then, by 8pm or so on Friday, it was nose to the grindstone. We were screen sharing with one another basically the whole jam so that we could compare notes and debug together. This was our first time working together, so it was also good to see each other’s workflow.

By maybe 8pm on Saturday, we had most of the mechanics finished. There were a few bugs, but the goal was to focus on finishing a reasonable number of levels and polish up the presentation. We didn’t have a single menu nor a reasonable order to our few levels!

We hit our stride, but it was still a lot to do in less than 12 hours. Especially if we wanted to get any sleep. With some final wraps — and deciding to let a few bugs slide — we submitted the Jam at 4am and hit the hay.

Next morning, the levels were all released and I spent some time playing them. It was amazing seeing so many different ideas and reflect on my own. Some favorites linked below, or check out the full Jam here!

What Went Well

Cade and I split responsibilities up a bit on this project, since I had used GDScript before and felt comfortable programming while he designed the levels. I was impressed by how well separated those roles could be, with the two of us pushing commits back and forth over Git without needing to resolve too many merge conflicts.

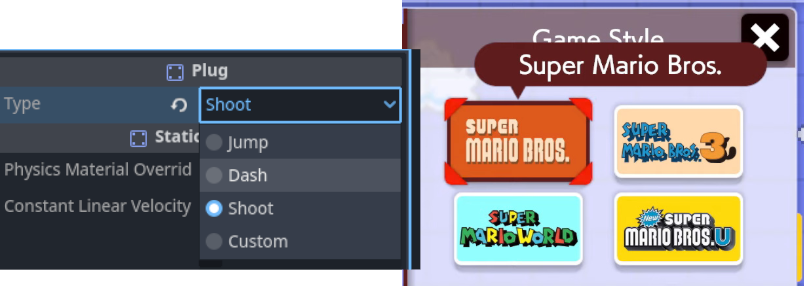

Cade was able to design the level using Scenes that contained only a Sprite2D, and then I was able to build some of those… behind the Scenes 🥁 They are a powerful way to create a higher-order object, and by exposing variables using @export, you can allow them to be customized in the editor — It’s like Mario Maker!

Generally, our iteration was super fast, which I can applaud Godot for. Beyond syncing our changes across branches, using a TileMap made it easy to sketch out levels and populate them later. You can even reload changes within the Godot debugger, while the game is running!

From a tooling perspective, I tried to use Obsidian to do some personal planning and thinking in this project. Sketching using Excalidraw was great for diagramming and screensharing simultaneously, though sharing the notes themselves were a little harder. Publishing was also super easy. Godot default settings work as an export both to Itch and to the Web.

The game also ended up quite graphically appealing, thanks in no small part to the Kenney assets. Some simple animations, particles, and sounds gave our game a lot more oomph. It’s part of what I think would stand pretty well if we went back and revisited the game.

What Could Improve

Before we get into improvements, I first want to applaud Cade for his first time using Godot. While it shares some features with big IDEs like Unity and Unreal Engine, it was still a totally new environment that we were trying to rapidly prototype in. In hindsight, we both definitely should have gotten more practice before rather than learning during the Jam.

Technically

There were a few rabbit holes we went down which didn’t end up being valuable which we could have avoided with some testing ahead of time. For example, we had a tile-based game and wanted to use TileMapLayers to build out levels. At first, we thought using a SceneCollection within could be a good way to place tiles that were composable via Scenes.

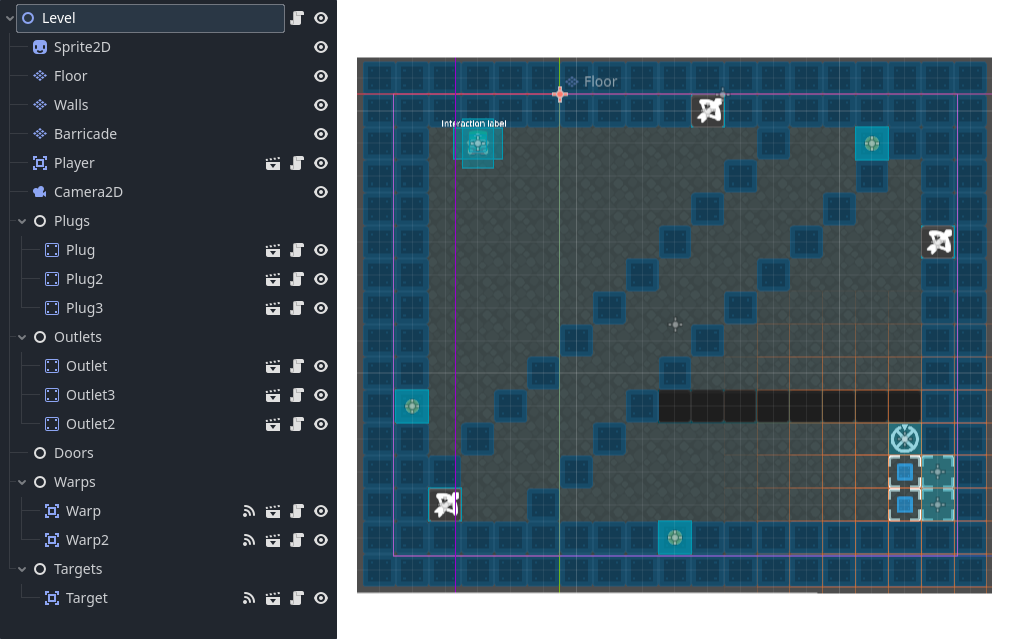

Screenshots of our Scene tree (left) and the

TileMapLayereditor (right)

The problem was that (at least from our testing) we couldn’t address individual tiles with the @export variables, meaning that we couldn’t paint those tiles using a TileMapLayer. Perhaps there’s a clever solution to this, but we had limited time, so we needed to find another approach! We ended up just using individual Scenes for configurable entities, but still leveraged TileMapLayer for large, “dumb” components like walls or holes, which were just collision-based.

There were also some minor polish improvements we could have made, like:

- submitting a debug build, without some of the performance optimizations

- ensuring the UI would translate well to the web

- adding controls to play on a mobile device, which is a great way to share But ultimately, time was such a crunch that I don’t regret the choices we made.

In Gameplay

A common piece of feedback I got from friends I sent the game to was, “I didn’t understand what the plugs did.” Moving Perry around was straightforward, but in a puzzle game, it’s important your players understand how something works so that you can build levels which require them to interact with it in a way they haven’t thought of yet.

If I were to remake some levels, I might add a few near the beginning that don’t even give Perry a power, they’re just used for unlocking doors. There’s likely some design space for simple puzzles where you leave an impassable trail behind you when connecting plugs to outlets, but then you can quickly move on to unlocking a power.

I also think we could have spent more time focusing on each of the individual mechanics we had put into the game. There are some introductory levels which use each of the mechanics, but I think there was still plenty of design space left to build puzzles around each, individually. If only we had the time.

In our initial design of the game, we actually had considered a branching path of levels where you could unlock a power-up permanently, but as it goes for most game jams, scope had to be cut. The Super Plug Room would have contained a puzzle solvable using each different abilities, opening a door that would take you to levels where you could always jump, dash, or shoot!

flowchart LR T(Tutorial &<br/> Early Levels) P(Super<br/>Plug Room) T --> P J(Jump Puzzles) S(Shoot Puzzles) D(Dash Puzzles) P <--> J P <--> S P <--> D

Takeaways

My friend Tyler once said, “writing sucks, having written is amazing”. And I think the same is true for game jams. There’s a ton of chaos and grind during the event, but by the end, it’s so satisfying to look back at what you’ve accomplished, no matter what state it’s in.

My biggest takeaway from the Kenney Jam is that there’s more that can be done before the jam than I expected. For starters, refreshing skills in Godot would have been a good idea, but even prepping a game template for Godot would have helped us hit the ground running.

I also was reminded that programming best-practices don’t always make sense in a game developer’s world! I shied away from global variables early on, but they ended up being useful for things you want to be global, like sounds, input, etc.

And lastly, there’s always less time than you think. Even if I hadn’t worked on Friday and we didn’t sleep at all, there’s still no way we would have finished. But that’s the fun of a jam: getting an idea out there and seeing what sticks. Can’t wait for the next one!

Appendix

Here are some other related links out to things from the jam. I won’t add much commentary, since there are so many, but feel free to check them out!

Favorites from the Jam

In no particular order:

Referenced Articles

- Kenney assets, which we used for the Jam! Seriously, if you have not taken a look at everything Kenney has given for free, I would recommend taking a look.

- freesound.org, another excellent source for assets in your games, or really anything! Have been using this ever since I was a kid.

- Grid-based movement tutorial by KidsCanCode, which we used as a starting point and teaches a few more advanced mechanics around raycasting and property tweening.

- 2D Interaction example by QuebleGameDev, which I used as a reference for building some of the systems in Perry’s Power-Ups.

- Godot’s Signal docs, which I think are a super powerful system, especially if you like an Entity-Component-System way of thinking.

- This Godot game template! It adds a lot of menu support that’s common for most games. I ended up using this as a reference instead, since I didn’t discover it until late, but I would definitely consider forking this for my next jam.