2020: Disco Elysium

Disco Elysium

Release Date Developer Publisher 15 Oct 2019 ZA/UM ZA/UM

Disco Elysium takes players back to old-school, 1.5-dimension, dice-based RPGs — like the first couple Fallout games or Divinity — but with a fervent focus on witty dialogue and political discourse over high-octane combat and expendable characters. The result is a surreal, though grounded story, with over 6,000 years of in-game folk history using a creative way of divulging player information to keep replays interesting.

I have many accolades for Disco Elysium, but I should also be upfront that it involves reading. A lot of reading. The (now-completely) voice acted script gives characters gravitas and some extra legs to the slow-burning plot, but you’ll still need to pay attention to the dialogue and probably won’t like this game much if you have an aversion to reading.

The reward, though, for taking the patience to read through the experience is a tightly-knit web of stories, interconnected and built up by small choices made by the player. The protagonist — a dilapidated drunk — has amnesia, giving players the ability to make choices on their own, while your partner, Kim Kitsuragi, tries to keep the case progress roughly on track. Along the way, the protagonist will learn more about their own history while digging into the identities of a variety of characters in the game’s alternative-reality, post-Communist revolution city of Revachol.

From a mechanics perspective, it’s clear that the game was developed as an extension of classic tabletop RPGs. Skill checks involve some player stat being added to a roll of two six-sided dice with the minimum roll — regardless of added bonus — being an automatic fail while the maximum is an automatic success! This makes any skill attempt possible, though in order to repeat a failed attempt, players must level up the corresponding skill.

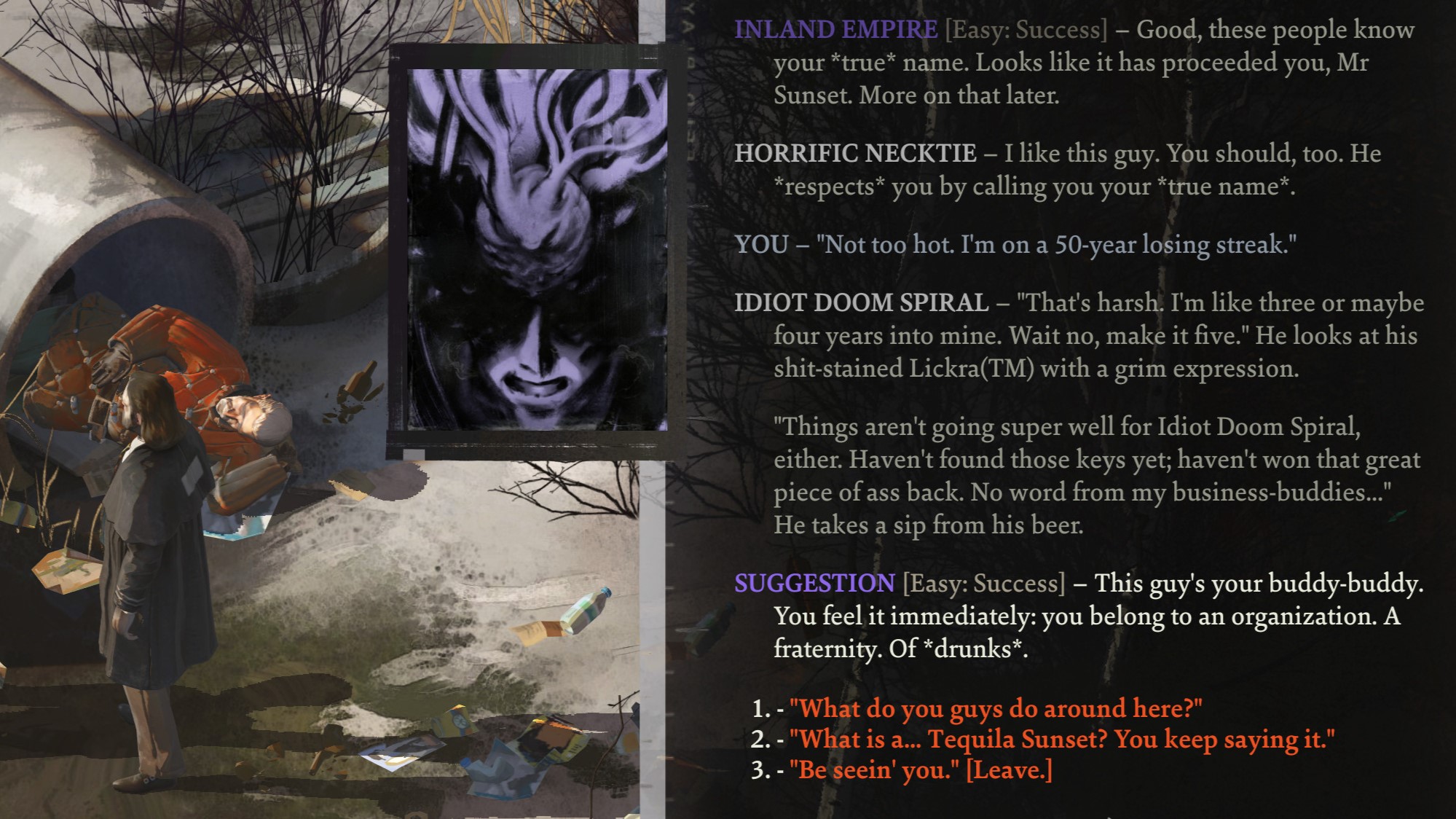

The skills are also woven into the experience via in-game personalities. Each skill is a voice, talking to the protagonist (or sometimes, to each other) from inside his head. They also typically only chime in when passing a corresponding skill check, meaning missed checks are often hidden from the player. This allows for a lot of hidden replayability, as scenes in the game may have a completely new direction if you’re more in-tune with the drug-addicted side of the protagonist rather than the detective-oriented one.

The Inland Empire and Suggestion skills (and even my neck tie!) chime in to give extra insight to a conversation with some drunkards in Revachol.

The core choices of Disco Elysium come from the conversations in your head and with the characters of the city. The player will frequently be forced to defend their actions via historically-reimagined, ideological equivalents (often with the same name) like communism or neoliberalism. However, the conversational adversaries may not always be swayed by the same arguments or players may not be able to use certain ideologies to defend specific actions.

Throughout a playthrough, the game then analyzes which ideology you “truly” believe in — based on your responses — and can insert new options into dialogue, encouraging the player to commit to a belief. While this may not be the radical, story-altering experience some choice-enthusiasts will salivate over, the choices feel “deeper” in that they permeate throughout most of the game.

The mystery the player begins solving at the start is no longer a focal point. Instead, the player might be focused on how they can convince everyone of their political agenda, or the variety of uncoverable intrigue plots: Who killed the old head of the Union? Where is the red-haired woman from the motel? What turned the protagonist from heroic detective to dreary-eyed, degenerate drug user?

If you want the answers, you’ll have to play the game and see what your version of the events look like!