Spritfarer

Release Date Developer Publisher 18 Aug 2021 Thunder Lotus Games Thunder Lotus Games

Overview

Spiritfarer is “a cozy game about dying.” You play as Stella, a young woman tasked with ferrying the dead, which, while it sounds morbid, actually involves a relaxing sail around various islands, completing the cute — though sometimes tedious — last wishes of spirits before they can move onward.

The first thing that often jumps out to players is the sheer beauty of the game. Thuder Lotus is known for their hand-drawn visuals which bring incredible staying power to Spiritfarer. Combined with polish and clever redesigns of the Management genre, the game is able to minimize — though not completely avoid — the burnout often associated with this style of game.

Resource Management

At its core, the game is focused on resource management. You have a ship to sail around, collecting resources to construct buildings, upgrade dwellings, improve your ship, and discover new frontiers.

Teaching a Complex System

There are a lot of mechanics and projects to attend to on your ship. In fact, it’s one of the ways Spiritfarer can stay so fun — there’s always something aboard calling your name. Whether it’s gardening, cooking, weaving, or playing music, completing tasks on the ship feels seamless with players rarely having to think about “what’s next”. It just flows.

The dinghy at the start of the game has some room for only a few buildings so that the player gradually learns about each mechanic in the game.

The abundance of activities could have been overwhelming to a player starting the game, but Spiritfarer makes the smart choice to slowly drip these offerings out over the course of the game. Most new activities come from new buildings created on the ship: once you create the Loom, you can weave; after you have the Sawmill, you can manufacture planks; etc.

Each activity has a minigame which players complete to earn the output resources. Some are simpler, like watering the plants in the garden. Others can be more complex, like smelting ore at the right temperature to create ingots.

In both cases, the player now has something new to do, but they’re able to introduce it at their own pace. After all, there’s no requirement to build a garden aboard the ship, but curious players looking for a new challenge will do so and learn as they go.

Players are also given detailed (though sometimes over-explained) tutorials from the spirits that specialize in each craft. For example, the starting spirit, Gwen, teaches you how to use the Loom, of which she is also a fan.

By the end of the game, the player’s ship has grown into a colossal barge, with an abundance of important buildings — each with their own mechanics — aboard.

The incremental improvements and discovery of new mechanics motivates the player to continue playing while also creating a learning curve of complexity as both your ship and its horizons expand.

Balancing Simplicity with Replayability

Management games like Animal Crossing, Stardew Valley, or Factorio are typically full of minigames to add some spice to acquiring resources, crafting, etc. The implementation of these mini games is an important part of the player experience and can vastly change the game, even for the same resource.

For example, both Animal Crossing and Stardew Valley have a fishing minigame. In Animal Crossing, the mechanics are straightforward — if you see the shadow of a fish in the water, you can throw out your line and wait for it to approach your bobber. Then, once you get a bite, press A and reel it in! As long as you press the button fast enough, the fish is yours.

However, in Stardew Valley, the fish don’t appear in the water. Instead, you cast out your line wherever you’d like. Eventually, a fish will bite and then the minigame starts. A meter appears near your character, and you need to hold A to keep the yellow bar over a moving fish icon.

|  |

|---|

Animal Crossing’s fishing is simpler and more approachable, but the added complexity of fishing in Stardew Valley may entice players to practice and return to it more often.

The trade-off the two games make is between the depth of gameplay, the experience to the player, and how it gates additional content or resources.

Animal Crossing creates a streamlined experience, possibly targeted at more casual players, but at a cost of low skill-expression (some fish give you less time to press A before fleeing). As a new player, it’s easy to get into fishing and see what waits for you out in the water. However, players may eventually tire of the repetitive experience, especially since the main reason to fish (in my opinion) is to populate the museum, so once you catch a fish once, you probably aren’t very interested in catching it again.

On the other hand, Stardew Valley gives players a minigame with deeper mechanics at a cost of higher complexity. There are bobbers you can use to change how the yellow bar moves and different fish have various patterns of movement — sometimes you can even recognize which fish you’re going to catch before seeing it!

The added nuance encourages players to return to fishing when they discover a new bobber or unlock bait, but fishing initially may have a higher ramp-up. There’s even progression baked into the game: your yellow bar starts very small but grows as your character levels up, so while “core” players may appreciate the challenge, it can be difficult to start out as a new player.

|  |

|---|

Spiritfarer strikes a balance between approachability and complexity with its fishing minigame.

Now let’s consider Spiritfarer’s fishing minigame. The gameplay is similar to Stardew Valley: players can fish whenever they’d like, casting their line into the water and pressing A when there’s a bite. Instead of a meter, the fish will move away from the player while you can hold A to reel in the fish. If the line is in danger of snapping, the entire rod will turn from vibrant yellow to deep crimson until, if the player refuses to let go, the line will snap. You catch the fish by pulling it in close enough without snapping the line.

At its core, Spiritfarer's fishing game echoes the Stardew Valley formula, but it manages to improve the player experience in two ways:

First, the player initially cannot snap the line at all, and therefore will always catch the first. Early on, the game is intent on teaching players how to fish, though you are only able to catch a subset of fish (as well as lots of trash, like the classic Old Shoe). This allows players to learn the minigame with low-stakes, especially since there are a bunch of other activities on the ship they could be doing instead.

Second, even once the line-snapping mechanic is introduced, it’s still much harder to lose the fish than in Stardew Valley. The line will snap if the player doesn’t respect the line turning red, but otherwise the fish will stay on the line. Comparably, in Stardew Valley, the green meter can reach zero if you aren’t keeping the bar over the fish enough, at which point it will flee. New Spiritfarer players will still be able to catch fish, even if it takes them longer than someone more experienced.

By lowering the skill floor, Spiritfarer’s fishing is approachable, but still allows for deeper player expression. The developers hit a sweet-spot where fishing is relaxing but also fun to return to. I often found myself casting my line in new waters, hoping to find some new fish. There’s even areas on the map for fishing-specific events, but I’ll leave that to you to play!

Scaling without Staling

Another tricky balancing act management games have to play is around scaling the game with player progress. There should be a sense of active progression throughout the game — players want to feel like they’re improving and be able to grow with the game.

In a management game, where progress is often gated by the acquisition of resources, scale typically revolves around how to balance the sources and sinks of resources. This allows players to progress semi-linearly with respect to the non-linear scaling of incoming resources.

In Factorio, for example, creating higher-level components requires significantly more materials and time.

Factorio Level 3 assembly machine recipe.

A Level 3 assembling machine requires two Level 2 assembling machines, which means upgrading all of your Level 2 assembling machines is quite an expensive operation.

This works in a game where crafting and automation go hand-in-hand. The player is incentivized to build things not by hand, but by a chained-together array of mining rigs, belts, and assembly machines that all combine together to make Factorio fun! While it can be increasingly expensive to craft upgraded items, that is an intentional game mechanic so that players are, well, actually playing Factorio.

But for a game like Animal Crossing, for example, where crafting, despite it’s fun and peppy animation, takes a tedious amount of time (~3 sec per craft). This may not seem like a long time, but if you are crafting something expendable, like bait, you’ll spend minutes crafting supplies that will be used up fairly quickly. As a result, Animal Crossing doesn’t have many recipes that require multiple steps of crafting (i.e. Craft A to make B to make C) so that players are rarely spending copious amounts of time crafting, since it’s only a minor component of the game — at least, compared to Factorio.

The crafting experience in Animal Crossing prioritizes its whimsical art style and snappy animations.

As a result, crafting in Animal Crossing can — after enough time — feel like a gateway to playing the game, rather than a fun mechanic to enjoy. Crafting can become a chore because there’s not much player expression in the process.

In Factorio, automating crafting is exciting. Once you have a few assembling machines doing your bidding, you can stop spending time crafting basic components and start thinking about what you’ll build next and — perhaps more importantly — how you’ll accomplish it.

But in Animal Crossing, crafting is done out of necessity. If you want to catch a bug, you’ll need to craft a new net after yours breaks.

The tradeoff, though, similar to the fishing example from the previous section, is approachability. Factorio is far from the casual experience that is Animal Crossing. And I don’t think Factorio is “better” than Animal Crossing or vice-versa. The key point is that balancing the feel and speed of progression in the game is a necessary consideration for game developers.

So now, let’s consider how Spiritfarer does it. First, let’s examine all of the different materials:

Spiritfarer Resources

| Class | Stages | Types |

|---|---|---|

| Wood | Logs, Planks | Maple, Oak, Ash, Pine |

| Rocks | Rock, Powder | Limestone, Coal, Slate, Quartz, Marble |

| Metals | Ore, Ingots, Sheets | Copper, Iron, Aluminum, Zinc, Silver, Gold, Pulsar |

| Cloths | Fibre, Thread, Fabric | Linen, Wool, Cotton, Nebula, Silk |

| Food | Seeds, Fruits & Veggies, Fish, Meat, Dishes | Apples, Turnips, Corn, Mackerel, and many more |

Wow, looks like a lot! But each “Class” of materials are all harvested and then crafted in roughly the same way:

- Trees, regardless of type, are chopped down into Logs and can then be refined into planks at the Sawmill.

- Fibre is obtained from plants or sheep, then placed in the Loom to be woven into thread which can be put in the Loom again to be re-woven into fabric.

- Food is placed in the kitchen oven to be turned into a variety of meals.

Each of these processes involves another minigame where players are challenged to improve their skills, though the game maintains a low skill floor to ensure inexperienced players will not be gated by their inability to saw logs, for example.

|  |  |

|---|

Examples of the various Spiritfarer crafting minigames. From left to right, the Sawmill, the Loom, and the Kitchen.

In the Sawmill minigame, players must align the blade with the dotted, yellow line for each log they saw. Based on how well aligned it is, the players will get 1 - 4 Planks. Similar to fishing, the design allows experienced players to benefit from higher yields as they improve, while preventing players from being completely unable to produce wood if they don’t get it perfectly right.

Notably, the scale for Spiritfarer is done via a marginal increase in difficulty, rather than quantity. Instead of requiring players to produce more of one type of resource, like we saw in Factorio, they must manufacture new types of resources using a slightly harder variant of a minigame.

For example, going back to the Sawmill, the type of wood you first find, Maple, is easiest to saw, requiring only one or two precise movements from the player. However, the later types of wood, like Oak or Ash, require the player to cut the wood more acutely.

Thanks to the variable yield mechanic discussed above, the player will always get some output, but they will be motivated to continue honing their skills at the Sawmill if it means they’ll get the coveted 4 planks instead of 1, 2, or 3.

Compared to Animal Crossing, this also means that players can have fun returning to a crafting minigame, which helps reduce burnout. While it may not be the most fun part of the game, (the Crusher, for example, gets old quickly — you just press A over and over) Spiritfarer brings life to an overlooked part of other management games, allowing crafting to scale into the late-game without getting stale.

Interwoven Design

Another way that Spiritfarer keeps the minigames exciting and at the forefront of players’ minds is by chaining them together, so that players must bounce between a few different locations to accomplish their goals.

Let’s say you want to put one of the spirits in a good mood, since if you do, they’ll help complete some chores around the ship. One of the best ways to do so is by cooking a meal they love. The Kitchen is where you can combine ingredients to make some food, but you’ll need some quality ingredients first, either from the Farm or the Garden — better get to planting!

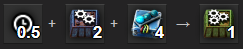

As you can see from this example, players must complete a few different minigames in order to do what they want. Growing food leads to cooking meals which raises morale onboard and finally, the happy spirits will be more helpful. And this is one of many different “chained” systems that enables the player to always have something to do next.

There are a variety of interwoven systems in which players can make the spirits onboard the ship happy.

Some specific resources also require multiple minigames to be completed. A key component, Fireglow, is obtained via a platforming minigame, but then must be grown in the garden before it can be used for crafting or cooking. Another resource, sunflower seeds, initially only seem useful for planting over and over (a harvested sunflower only yields more seeds) until the Crusher is unlocked, allowing you to smash the seeds into useful oil.

Each combination of chained minigames gives variety to the player, but also distinction between various resources and tasks. Sunflower seeds feel so different than other seeds, and stick out in your mind, because of the different ways you have to use them.

Different resources exist in Spiritfarer not just to provide variety in crafting and upgrades, but also to give players a different experience as they harvest each new crop. Rather than just watering the plants every day until you can sell them, players may cook, crush, sell, or give away their crops through a woven, intermingled set of systems.

Spirit Interaction

Making spirits happy isn’t the only way each of the characters touch the other systems in the game. Many spirits are tied to specific minigames or events, giving them a specific time to shine and develop as you play.

Olga the turtle serves as both a character to chat with about the latest gossip and also as a “bank” to invest resources into.

The turtle sisters, such as Olga (above), players can talk to and learn the lore about the areas you’re sailing around — they each even have their own distinct personalities! But the turtle also act as an in-game bank where you can plant a log or piece of ore on their back for it to grow into a tree or mineral deposit. Players can then return later to get some more rumors and resources.

Players are also encouraged to learn about each spirit, discovering their favorite (and least favorite) foods, completing their odd last requests, and eventually hearing their story on their way to the Everdoor.

The mood menu reminds players about how to make a spirit happy and how their mood affects their behavior.

The variety of favorite foods and requests encourage the player to explore the intricacies of each system. A spirit that dislikes meat (which can only be bought) means that you’ll need to start growing some food aboard the ship to make them happy. A request that requires materials you haven’t yet found encourages players to explore new horizons.

By weaving the crafting minigames and exploration mechanics with each spirit, the game feels like a cohesive unit, greater than the sum of its parts.

Platforming

While Spiritfarer is mostly a resource management game, there is a surprising amount of platforming with a lot of intent behind the design. Players double-jump, zipline, and glide around each island that they explore, but the most interesting platforming challenge is the minigames completed on the ship.

As players expand their ferry with new buildings and houses for the spirits, they must place each variably-shaped building onto the construction grid. Each building is also covered with ladders, forcing players to choose if they want to align a big ladder that stretches from top-to-bottom or maximize space by squeezing buildings as efficiently as possible.

Buildings of all shapes and sizes must be placed within the bounds of the construction grid (which expands as players upgrade their ship).

But the real genius behind the layout comes from the different platforming minigames that require the player to quickly jump around their boat to gather special resources. For example, in the Comet minigame (below), players must quickly gather comet shards before they fizzle out, requiring nimble movement around the barge in order to obtain as much as they can.

What’s more, each game challenges the platforming layout of your ship. In the Lightning minigame, resources always come from above. In others, the resources may come from the sides or even underneath.

The interwoven mechanics allows one relatively simple idea, laying out buildings on your ship, to require a lot of interesting thought from the players. And, like we saw when exploring the skill curve of Spiritfarer, it’s okay if players don’t make these consideration, but there’s a high skill ceiling for expression.

Polished, Consistent Experience

One of the most striking parts of the game is the art. Hand-drawn, consistent, beautiful. But the polish doesn’t stop at the art — both the user and narrative experiences shine throughout a player’s journey through Spiritfarer. It’s here where the game is able to push the chill energy hardest.

In Art

We can start with the obvious: the art. If you haven’t been blown away by the games art, hopefully a few glamour shots will do the trick:

A lot of work has been put into making the game look beautiful and cohesive. Immersion is constant, since everything is carefully composed within each scene.

In addition, the animations and sounds are extremely satisfying, which is important as you will experience many of them over and over, like watering plants, cooking food in the oven, or casting the fishing rod.

Sadly, it’s hard to convey the artistic experience via text given the nature of visual art. I’d recommend watching any gameplay video or, of course, giving the game a try!

User Experience

Something we can talk about more is the player’s experience: the controls, pacing, and interface (UI).

Interface

The UI serves to highlight the beauty of the game’s art. When discovering a new island, for example, the game will pause and fade to a distant landscape of the nearby isle.

Not only does this force the player to take a breath and enjoy the watercolor art, but it also encourages them to explore by giving them a taste of what they might find on the island: A resource-heavy island might show a dense forest, while an inhabited one would be littered with buildings and lights.

What the player sees when discovering the island of Hummingberg.

To further highlight the aesthetic, there are even controls to hide the UI entirely so that the player can bask in the glory of hours of work Spiritfarer’s art team must have spent bringing the world to life.

Controls

In general, the button mappings are oriented for simplicity. There are four core action buttons and the left stick / d-pad used for movement. In theory, the game could be played with a SNES controller, or in my case, a single Switch JoyCon.

It’s worth noting that I played Spiritfarer on Switch, so only played using a controller. Since the game is also on PC, I could imagine certain systems (like building placements) to work differently with a mouse and keyboard.

Gameplay felt satisfying from a control perspective — in particular jumping around with all the various flip and glide animations was amazing. My only gripe would be how consistently I accidentally watered the wrong plant in the garden, though that feels like an extreme nit.

Personal Issues with Pacing

Pacing was, in my experience, the worst part of the game. And part of this I take responsibility for: I went pretty hard on optimizing everything onboard the ship, and that left me in a few positions where I was out of other tasks to do.

As a result, I was stuck, waiting to discover a key resource that required the plot from a particular spirit to advance. This lead to me bouncing between islands, gathering resources, sure, but more as a chore to kill time rather than because I needed them.

Eventually, I was able to get the resource I needed and move on, but the damage had been done: I had started to feel burnt out.

Now, in general, the game leaves the player with lots to do. Even during my downtime, I was still able to get lots of crafting, cooking, planting, and so on done. But when the drip of excitement dries up in a management game, players will often feel like the tasks are chores more than activities or minigames.

I think my personal experience of Spiritfarer’s pacing is an exception rather than a norm, but I encourage you to find out for yourself!

Narrative Polish

The unique spirits aboard the ship help bring the game to life. Like Stardew Valley, each player will get to meet all the same spirits (or villagers) during the course of their playthrough. While this means there’s less variety player-to-player, the result is much deeper interaction with each spirit. They each have their own personality, likes, dislikes, and activites you’ll see them engaged in throughout your journey.

For example, when visiting islands to gather supplies, you’ll often see the spirits gathering berries or buying seeds or thread. This takes some of the pressure off of the player to provide everything aboard the ship, but it also makes spirits feel human. They have desires and actions outside of the player and act on them based on the location.

You’re also welcome to interact with each spirit as much (or as little) as you’d like. They live aboard the ship, meandering around between the different buildings (also based on their interests). While you may need to keep them fed, if you otherwise don’t like a spirit very much, you can just keep your distance.

You first meet the spirits in “NPC” form, having to guess who they are from their silhouette. Once aboard, they reveal themselves, though you can still remember them via their outline.

|  |

|---|

The striking silhouette creates clear distinction between spirits, even after they are revealed once aboard the ship.

However, getting to know each spirit is fairly rewarding. As previously mentioned, they each have their likes and dislikes, but eventually they’ll make extremely specific requests, so the player gets to be a part of their final moments.

And what makes the heart-wrenching plotlines of the spirits even more gripping is that many of the stories are based on real-life events from the developers.

For example (minor spoiler)

Alice, an adorable, old hedgehog is based on the grandmother of one of the developers who passed away during the game’s creation. Both suffered from dementia, revealed in the game by Alice’s frequent asks for the player to build her a house on the ship, even after having already done so.

By the end of the game, each spirit had stuck with me in some way. I found them extremely memorable and easily distinguishable — two important accolades of character design.

Co-op

The two-player couch co-op in Spiritfarer was not something I tried. In my research, it seemed like the main appeal is to use Dandelion (your pet cat) to complete some of the managerial tasks around the ship.

Frankly, since I never felt inhibited by any of the chores on the ship (I was hindered by the narrative pacing, occasionally, which I complained about above), it didn’t seem like there’d be a ton for a second player to do.

Again, I welcome experimentation and exploration. If you loved the co-op experience in Spiritfarer, share your thoughts!

Conclusion

Hopefully, if you’ve read this far, you agree with me that Spiritfarer tries very hard to avoid players burning out. And, for the most part, they did a good job. There’s a reason the first third of my playthrough was completed in just a weekend: the game can rope players into the “just one more task” mindset that causes them to lose track of time.

I think this game would appeal to those who want a casual management game, like Animal Crossing, but with a few additional mechanics, like platforming, and a powerful narrative element.

You may instead want to pass on this game if you find repetitive tasks extremely exhausting, you want more action or control-intensive player expression, or if a narrative isn’t enough to push you forward in a game.

Overall, while I believe the game overstays its welcome just a touch (much like many of the spirits aboard the ship, or maybe this post) I would recommend checking it out and seeing how the formula for management games can be redefined.