Overview

I was recently looking through my library and was surprised how many years had passed since some of my favorite games were released. Many people are always focused on new titles — which makes sense, as fresh technology and ideas will deliver new experiences, building off of the learned techniques of the past — but I wanted to highlight some slightly older games that were prime at their release and might be worth revisiting.

This list will include some of my favorite titles, by year, mostly as a personal artifact of my experience, but also a log of how the industry has changed. Worth calling out that I’m listing these games based on the year I played them, not when they were actually released.

I think it’s also worth mentioning I see these as noteworthy games, not necessarily the best games; most titles are doing something new in the genre / space, even if execution isn’t perfect.

To me, it makes sense “spiritually” for this to be released (and updated) at the turn of the year, so I’m listing that as the release date. Without further ado, here are the games:

The Games

2014: The Stanley Parable

The Stanley Parable

Release Date Developer Publisher 17 Oct 2013 Galactic Cafe Galactic Cafe

The Stanley Parable was, for many reasons, one of the major breakthrough games in the walking simulator genre. While the gameplay mechanics are only a light series of choices the player makes on their adventure, the narrative mechanics are witty and respond to the players actions. This is a slight departure from previous games in the genre, like Myst, which instead focus almost entirely on puzzle-solving.

As a result, the game encourages you to play through it multiple times to experience the outcome of your choices, especially ones you might not otherwise have made. These stories then end in a variety of absurd ways from stopping a mind control device puppeteering everyone in the office to realizing the whole thing was all a dream.

When I first played through the game, the strange mechanics really stuck with me. In particular, it felt unlike so many other games, due to the focus on narrative, environment, and player interaction rather than novel gameplay mechanics.

While true, walking simulators can be a slog with poor pacing, The Stanley Parable’s eclectic variety of plot lines make discovering a new ending something players will want to pursue as each is distinct from the rest.

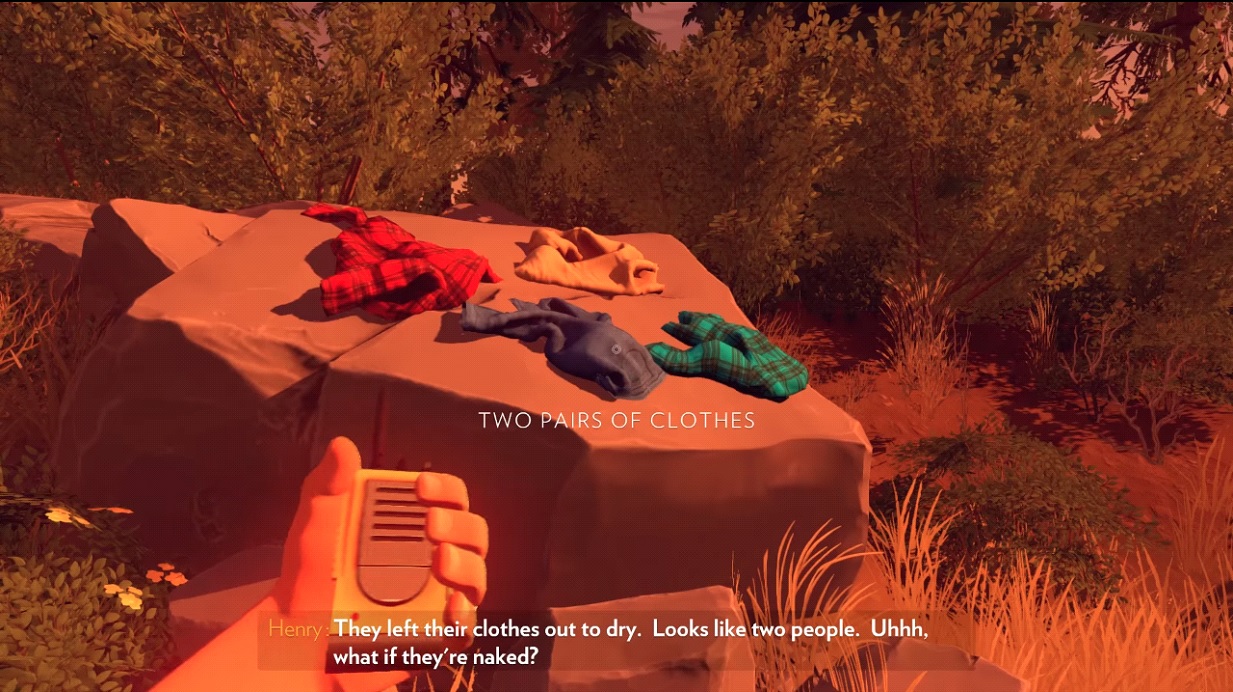

We can see this trend of variety as a means of enticing the player used by walking simulators released since. Firewatch, for example, involves the protagonist frequently communicating via walkie-talkie with a narrator-like, secondary character that responds to your actions, much like the Narrator in The Stanley Parable.

|  |

|---|

The games above, Firewatch (left) and What Remains of Edith Finch (right) use similar ideas of narrative-gameplay coupling as in The Stanley Parable.

Similarly, What Remains of Edith Finch contains a wide variety of disparate experiences as the player learns about the history of each member of the family. The interaction with the environment changes and feels tightly bound with the narrative, creating a satisfying “Aha!” moment for both solving the puzzle and uncovering new details within the story.

By coupling the narrative experience more tightly to the gameplay via responsive narration and impactful player choice, The Stanley Parable set the stage for the future of walking simulators and will remain a foundational piece in my video game repertoire.

2015: Fez

Fez

Release Date Developer Publisher 1 May 2013 (PC) Polytron Corporation Trapdoor

Despite some of the controversy around the release of the game and cancellation of the sequel, Fez caught my eye due to it’s novel, hybrid 2D / 3D technology, cryptic puzzles, and player-driven exploration and discovery. While completionists may be taken aback by how extremely detailed and arcane the solutions to certain puzzles are, the game allows players with a variety of experience to reach a satisfying ending.

Some added context, for those who haven’t played (spoilers abound!): Fez is a puzzle-platformer with a front-loaded focus on platforming and a back-loaded focus on puzzling. Players explore a detailed, 2D, pixel world using the protagonist’s ability to “rotate” the map between four “sides” of a 3D cube to change the location and orientation of platforms, secrets, or even the player.

The goal is to collect 32 cubes which will fuse together to fix the “glitch” that gave the protagonist, Gomez, the ability to rotate the world in the first place. However, while collecting 32 cubes is enough to beat the game, there is another set of 32 cubes, called anti-cubes, which are more difficult to find.

Realistically, anyone who beats the game will likely discover a few anti-cubes along the way, leaving some loose ends to explore further. This sort of scaling difficulty is what makes an esoteric game like Fez appeal to a wider audience: some will finish the game and call it there, while others will be intrigued by the anti-cubes and explore the depths of the game.

And there’s a lot of depth. The game itself has two distinct languages that the player must decode to solve puzzles. The first is more straightforward: A series of tetrominos which instruct the player to perform specific inputs (e.g. Up, Down, A, and B).

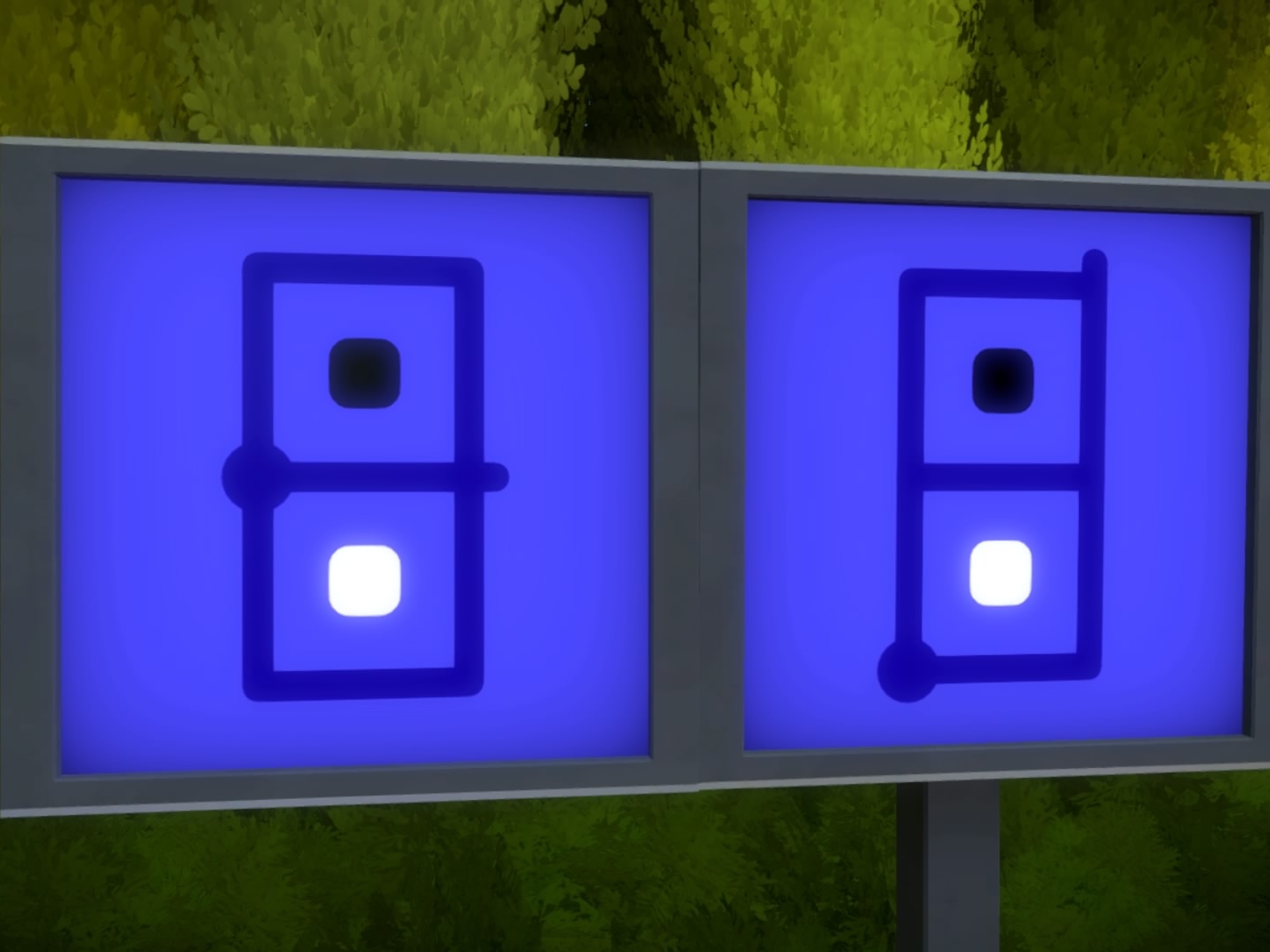

|  |

|---|

Players looking to uncover all of the secrets of Fez must learn to decode both the Tetromino symbols (left) and the Zu language (right).

The other language, referred to as “Zu”, is effectively a Dingbat font, where traditional, alphabet characters are replaced by symbols. The player can, over the course of the game, find rooms that clue them into the real letters associated with each symbol. From there, decoding messages just takes some pen, paper, and the discovered translations.

By its conclusion, players will feel Fez evolve from an exploratory platforming game, with lots of fresh ideas due to the 2D-3D mechanics, to an enigmatic puzzler, detailed enough to require handwritten notes. While other indie platformers like Braid or Celeste capture one side of the formula, it’s rare to see a game excel in multiple fields.

2016: Undertale

Undertale

Release Date Developer Publisher 15 Sep 2015 Toby Fox Toby Fox

Undertale is a difficult game to describe without playing it. A large part of the experience is based on subverting the typical expectations from JRPG titles, like Earthbound, which it was inspired by.

Players are offered the choice to play through the game either using the (intentionally) lackluster combat mechanics to defeat enemies, where they use a single type of attack to deal damage. Or they can learn how to befriend enemies, finishing combat via “mercy”.

The pacifist mechanic expands upon the games narrative-driven experience, allowing the player to learn more about common enemies or even bosses like now-famous Papyrus and Sans. But what drew me to the game is that the player is always offered the choice to follow up on these experiences. Someone looking to min-max the game might kill off each character in combat, wondering what all of the hype was about.

Of course, the player’s main guide at the beginning, Toriel, teaches the player how to actually play the game, by letting them know they shouldn’t try to harm the creatures of Undertale. But it’s not unreasonable that a player might ignore that approach as, initially, it also seems fairly dull.

Ultimately, Undertale is a game that requires players to get invested in its world to really appreciate the game. The goofy humor and heartfelt characters may draw many players in, though I’ve also seen players try to rush through the game like a standard JRPG, missing Undertale’s “true nature” and some of the great moments along the way. It’s hard to capture the humor and love put into this game, so I’d recommend trying it yourself.

2017: The Witness

The Witness

Release Date Developer Publisher 26 Jan 2016 Thekla, Inc. Thekla, Inc.

The Witness is one of my favorite puzzle games because it encapsulates the feeling of discovery using its language-less explanation of puzzles and concepts. The simple, “draw a line” puzzle mechanic is remixed in dozens of unique ways with each mechanic able to give players that “Aha!” moment.

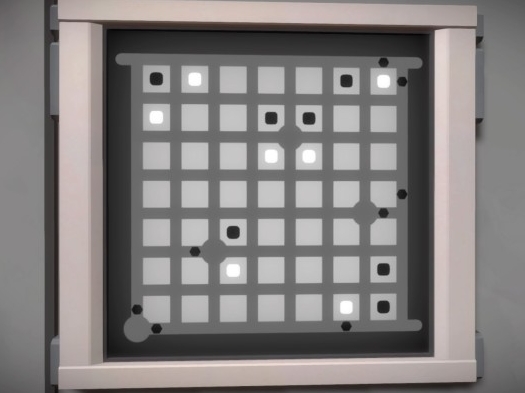

Early in the game, the puzzles are tight and straightforward, giving players the ability to experiment and figure out how new symbols influence the answer to each of the solvable panels throughout the island. As the puzzles increase in difficulty, those ideas may be challenged, forcing players to reconsider if the symbol actually means what they previously assumed.

|  |

|---|

The puzzles in The Witness start simple and are well-bounded so players can experiment and come to a solution. Later puzzles have an expanded amount of possible state, ensuring players prove they understand a concept.

By the end of The Witness, symbols are combined into new puzzles with further expanded state. To complete some of the game’s final puzzles, players must prove they understand the intricacies of each mechanic — and it would be almost impossible to give the correct answer without having that understanding due to their size.

From a technological perspective, the game is also quite impressive. It runs on a custom engine which enables the game to be played on iOS (though I wouldn’t recommend it). There was also substantial work done to combine levels into a single zone that could also be independently edited within version control.

Like Fez, there’s lots of stages of completion to the game. The player only needs to activate eight of the eleven lasers to reach the end, though even after completing the three additional levels, there are still hundreds of puzzles left to find, hidden all over the island. Years later, there’s still more I haven’t found in The Witness.

2018: Doki Doki Literature Club

Doki Doki Literature Club

Release Date Developer Publisher 22 Sep 2017 Team Salvato Team Salvato

This is one of the strangest games I’ve played. Before spoiling anything, I want to call out that the game is free and a fairly short (~4 hour) experience. I would recommend against reading into spoilers about the game, though be warned there is some graphic self-harm content (which will be very not obvious from the vibe of the game).

Doki Doki can be a hard game to talk about, since the game is a meta-heavy experience with multiple plots:

- The Plot: The story that happens to the characters as part of the visual novel game. The protagonist joins a high school literature club and writes poems in a thinly-veiled dating sim.

- The Meta Plot: The story that occurs between playthroughs of the game. Monika, the club’s leader (but not an option in the dating sim) gains sentience and modifies the game’s code to profess her love for the human player of the game.

The plot follows all the tropes of a visual novel. The poems you write are clearly meant to reflect the objectified character traits of the different love interests in the club. Your childhood friend professes her love to the protagonist on the first day of the game. The game’s assets are polished and hide the game’s horror/thriller meta-plot nicely inside of a cutesy anime game.

The meta plot shows the destructive nature of obsession and our flaws. The characters in the game are manipulated by Monika to showcase the extremes of their negative traits, poisoning the relationships the player forms during the visual novel. They’re eventually driven to killing themselves or deleted by Monika until she’s the only option remaining. In a way, the dating sim shell still did what is was meant to do — romance the player — but in a creepy twist on the genre.

To me, this game is noteworthy since its such a labor of love; it feels like it shouldn’t exist. A free, visual-novel game where you learn — via playing the extremely well-produced shell — that one of the personas is killing the others in order to be your favorite? Weird, fresh, and I’m there.

Since playing, they have released a “Plus” version of the game with additional storylines and endings, though I haven’t tried it yet. I’m not sure how much would be modified from the main story (or how they’d make certain mechanics work on the Switch, for example) but perhaps it’s worth revisiting after my trip here down memory lane.

2019: Return of the Obra Dinn

Return of the Obra Dinn

Release Date Developer Publisher 18 Oct 2019 (Switch) Lucas Pope 3909 LLC

Good detective games can be hard to find. Designers must work to balance the game so that it isn’t too hard to find important clues or uncover the mystery while still enabling player expression and keeping the joy of discovery.

Return of the Obra Dinn accomplishes this using an expanding tome of identities that the player fills in to denote which characters have perished, by what means, and who (if anyone) killed them. The book will inform the player they’re correct only when three identities are completely filled in (identity, means of death, and adversary). This ensures players are actually paying attention and filling things in while they go, but also allows some guesswork to help pave the way.

In addition to the mystery of deaths aboard the Obra Dinn, there are also other-worldly forces at work that make the in-game lore more interesting to explore.

For example, one of the the mermaids’ shells can be seen from the ship, even from the start (though the player will have to deduce this sparkling talisman throughout the story). Even aspects of the Memento Mori, the pocket watch which allows players to see into the snapshots of the past, has consistent rules it follows, further revealed by the storyline with the monkey paw, which illustrates how a remnant of the deceased is required to look back at the moment they died.

To me, Obra Dinn is a modern take on the detective game formula. There are innovative ways of enabling player expression (especially for the deceased who don’t have dedicated diorama entries for their demise) while also some in-game mysteries to explore, like how the mystical pocket watch enables your investigation. I’ve recently also enjoyed Case of the Golden Idol which uses similar mechanics and inner-world mysteries to drive an impressive, snapshot-based experience.

2020: Disco Elysium

Disco Elysium

Release Date Developer Publisher 15 Oct 2019 ZA/UM ZA/UM

Disco Elysium takes players back to old-school, 1.5-dimension, dice-based RPGs — like the first couple Fallout games or Divinity — but with a fervent focus on witty dialogue and political discourse over high-octane combat and expendable characters. The result is a surreal, though grounded story, with over 6,000 years of in-game folk history using a creative way of divulging player information to keep replays interesting.

I have many accolades for Disco Elysium, but I should also be upfront that it involves reading. A lot of reading. The (now-completely) voice acted script gives characters gravitas and some extra legs to the slow-burning plot, but you’ll still need to pay attention to the dialogue and probably won’t like this game much if you have an aversion to reading.

The reward, though, for taking the patience to read through the experience is a tightly-knit web of stories, interconnected and built up by small choices made by the player. The protagonist — a dilapidated drunk — has amnesia, giving players the ability to make choices on their own, while your partner, Kim Kitsuragi, tries to keep the case progress roughly on track. Along the way, the protagonist will learn more about their own history while digging into the identities of a variety of characters in the game’s alternative-reality, post-Communist revolution city of Revachol.

From a mechanics perspective, it’s clear that the game was developed as an extension of classic tabletop RPGs. Skill checks involve some player stat being added to a roll of two six-sided dice with the minimum roll — regardless of added bonus — being an automatic fail while the maximum is an automatic success! This makes any skill attempt possible, though in order to repeat a failed attempt, players must level up the corresponding skill.

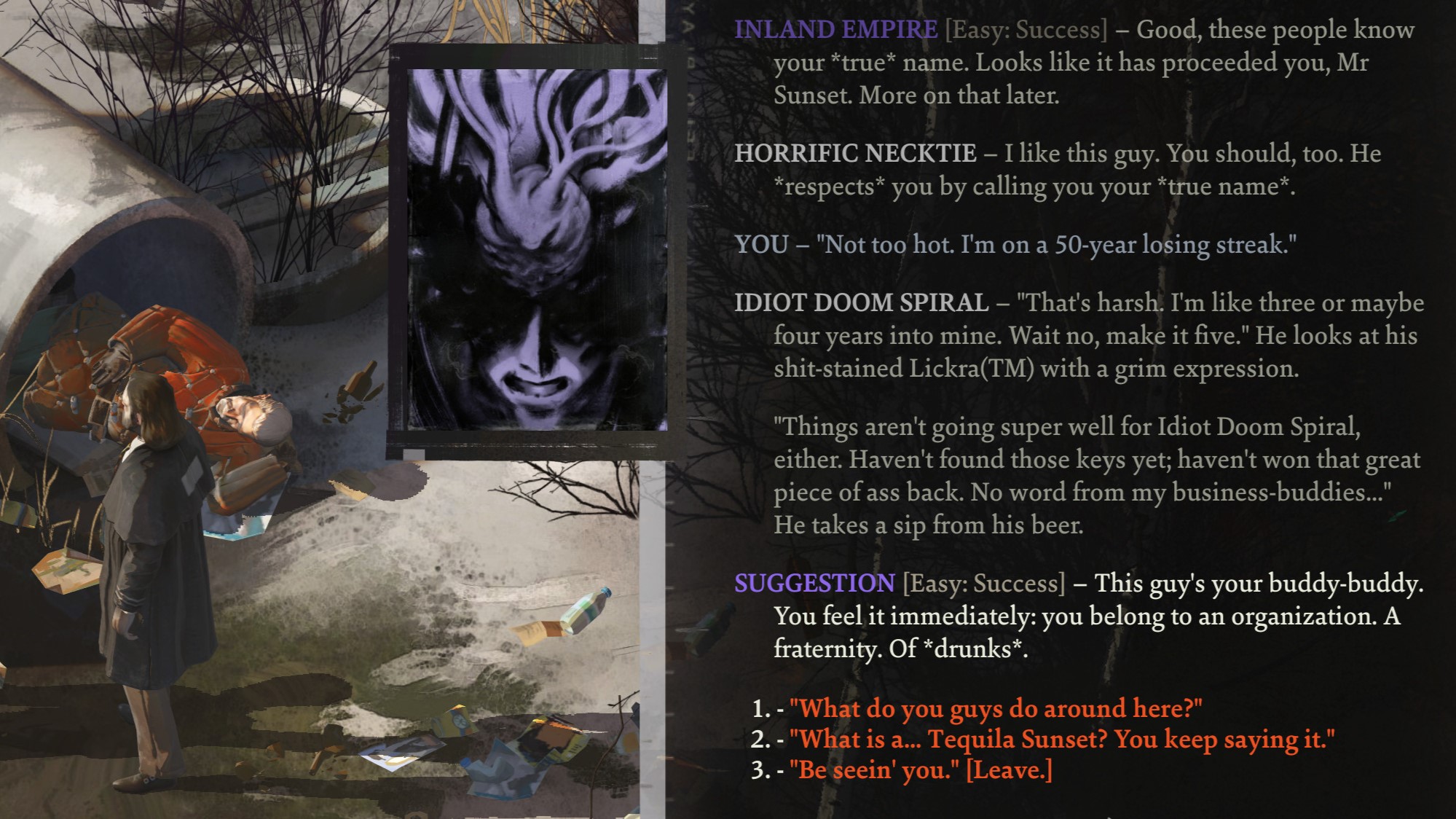

The skills are also woven into the experience via in-game personalities. Each skill is a voice, talking to the protagonist (or sometimes, to each other) from inside his head. They also typically only chime in when passing a corresponding skill check, meaning missed checks are often hidden from the player. This allows for a lot of hidden replayability, as scenes in the game may have a completely new direction if you’re more in-tune with the drug-addicted side of the protagonist rather than the detective-oriented one.

The Inland Empire and Suggestion skills (and even my neck tie!) chime in to give extra insight to a conversation with some drunkards in Revachol.

The core choices of Disco Elysium come from the conversations in your head and with the characters of the city. The player will frequently be forced to defend their actions via historically-reimagined, ideological equivalents (often with the same name) like communism or neoliberalism. However, the conversational adversaries may not always be swayed by the same arguments or players may not be able to use certain ideologies to defend specific actions.

Throughout a playthrough, the game then analyzes which ideology you “truly” believe in — based on your responses — and can insert new options into dialogue, encouraging the player to commit to a belief. While this may not be the radical, story-altering experience some choice-enthusiasts will salivate over, the choices feel “deeper” in that they permeate throughout most of the game.

The mystery the player begins solving at the start is no longer a focal point. Instead, the player might be focused on how they can convince everyone of their political agenda, or the variety of uncoverable intrigue plots: Who killed the old head of the Union? Where is the red-haired woman from the motel? What turned the protagonist from heroic detective to dreary-eyed, degenerate drug user?

If you want the answers, you’ll have to play the game and see what your version of the events look like!

2021: Inscryption

Inscryption

Release Date Developer Publisher 19 Oct 2021 (PC) Daniel Mullins Games Devolver Digital

Like Undertale, Inscryption is a hard gave to discuss in words alone. Partially because of the excessive amount of spoilers, though also in part because so much of the experience felt like it needed to be told in video game format, which is common for some of Dan Mullins’ other games like Pony Island and The Hex.

I would describe the game (spoiler free) as a roguelite deck-builder with some escape room elements thrown in. The cards in your deck talk to you as the player (sometimes even calling out your misplays) and give you hints to progress in both the micro-level cardgame and the macro-level “room” you must escape from.

To avoid any major spoilers, I’ll instead focus on the character design of the game’s three main bosses: The Trapper, The Angler, and The Prospector.

|  |  |

|---|

The masks of the three core bosses.

The first boss, The Trapper, the player will have already met during their adventure. Pelt cards can be purchased (as a random event) from The Trapper and sold to The Trader for strong cards at the short-term cost of adding the “useless” pelts in your deck.

As the player sees when facing off versus The Trapper, those pelts can also be used to remove enemy cards from the board. This is because, as revealed during the battle, The Trader is the same person — they even use the same upside-down mask! The pelt mechanic is well-designed for the first boss, since the player will already be aware of the existing mechanic but can now consider this twist for future runs. Maybe it’s worth keeping a pelt in the deck to use for the boss battle?

Next we have The Angler, an almost monstrous humanoid that frequently states, “Go fish” before using their signature hook to steal the most recently-played player card. Aside from a great pun, players will also have to watch out for the hook and play their cards carefully, always following up a strong card with a weak one that can afford to be hooked. While most of the battle is otherwise straightforward, a two-card swing is a big obstacle to constantly overcome when battling The Angler, forcing fresh decisions, regardless of the deck.

Finally, The Prospector is, in my opinion, the most difficult boss as he uses his pickaxe to immediately destroy your played cards (before following up with a powerful Bloodhound card). To counteract this, he also starts with a Pack Mule card in play that the player will want to quickly target, as it is chock full of cards to replenish your arsenal after it’s turned to gold by The Prospector’s axe.

Each boss requires the player to win two rounds (instead of the traditional one) and will follow-up with a powerful play after their first life is lost. This makes the game feel swing-y and satisfying to defeat a boss that has just recently wiped your entire board.

As my short description above demonstrates, the game has put in the work to create an enticing, replayable deck builder. And I didn’t even touch on the escape room antics and class, Dan Mullins’ meta-narrative! I would recommend this game spoiler-free, though find that the mechanics carry the game, even if you’re aware of the narrative.

2022: Neon White

Neon White

Release Date Developer Publisher 16 Jun 2022 (PC) Angel Matrix Annapurna Interactive

I liked Neon White a lot and plan to do a full, in-depth review of the game. I’ve also released an overview of how it encourages players to discover shortcuts and “trains” the speedrunning eye.

At a high-level, the game has great-feeling, finely-tuned movement controls and the performance makes snap-reloading levels (common in speed-running) seamless. While the storyline received some criticism for its anime tropes and cringe dialogue, I felt like some lines were taken out of context and are actually tongue in cheek.

I’m hoping friends will continue to pickup the game as I have loved comparing times.

My Reflection

This post took a while to write — more than I expected (I initially started it as a warm up for my Neon White review, though that might take even longer). It was satisfying to take a look at some old favorites and give a quick shoutout, despite the effort.

Plus, now that this list exists, I can update it with a much more manageable game-per-year. Who knows what 2023 will bring? Currently, I’ve got my eye on Pikmin 4, Jonathan Blow’s Sokoban-inspired game (if it ever comes out) and Tunic (which I haven’t played yet, so it still counts).