INFO

Release Date Developer Publisher Death’s Door 20 Jul 2021 (PC) Acid Nerve Devolver Digital Tunic 16 Mar 2022 (PC) Isometricorp Games Finji

Overview

I recently finished playing TUNIC, which reminded me a lot of Death’s Door, a game which I enjoyed but otherwise forgot about until considering how similar it is to TUNIC.

Both are isometric, Souls-like, Action-Adventure games starring a cutesy, animal protagonist. However, despite the similar core gameplay and appearance, each game varies in its execution.

This post aims to highlight why TUNIC stuck with me more than Death's Door, especially given their apparent similarity.

What Defines a Souls-like Game?

Since we’ll be discussing how Death’s Door and TUNIC each follow this format, we should clarify what it is. The definition has plenty of room for interpretation, so for the purposes of this article, I will be using my definition of Souls-like.

At a high-level, though, a good start might be:

From Wikipedia

A Souls-like is a subgenre of action role-playing and action-adventure games known for high levels of difficulty and emphasis on environmental storytelling.

The origin of the name comes from the Demon’s Souls and Dark Souls series by FromSoftware. For clarity, those specific games are instead referred to as Soulsborne games (derived to also include FromSoftware’s critically acclaimed Bloodborne).

I challenge the notion that high difficulty is a requirement for Souls-like games and will argue that it is instead an expectation from contemporary gamers.

I’ll expand on some other common themes that are found in Souls-like games, though there’s no official definition.

Redesigned Rest Points

One of the ways that Souls-like games are so unique (and classifiable) is the way in which players must heal their character.

The player is typically restricted from healing or resting except at designated sites. However, when the player chooses to do so, they will also heal or revive all enemies across the entire gameworld.

The recovery mechanic creates a powerful and exciting tension, since players can’t kill a few enemies, then just run back to the nearest checkpoint to heal up. To further compound the effect, enemies often take serious investment to kill, meaning players must decide if a rest will be worth fighting through familiar foes again.

This is also one of the ways that difficulty in Souls-like have become a presumption: As genre-experienced gamers grew in experience and more casual players were pushed out, more difficult enemies were required to continue fostering the kill-or-be-killed tension of combat.

This train of thought inspired me to think about how designers use health as a resource, which I split out to a separate article as it wasn't too related here.

Methodical Combat using Stamina

In order to maximize the impact of limited recovery, enemies in Souls-like games require players to carefully overpower them. Attacks from both the player and enemies are slow and will leave combatants wide open as the animation winds up and after the attack finishes.

Pattern recognition and patience is key to combat, rather than speed and damage output seen in hack-and-slash melee fighters. Players must analyze their enemies to find a moment of vulnerability to get a few hits in before retreating to safety.

The heavy usage of a stamina resource adds more difficulty. Players will be vulnerable or unable to perform specific abilities when out of stamina. But they also need to use the stamina to be effective in combat via dodge-rolls, empowered attacks, or by blocking enemies.

Iudex Gundyr, the first boss of Dark Souls III. The player must carefully manager their attacks in stamina to defeat the boss. He also eclipses the player, giving the appearance and feel of an unfair opponent.

This all culminates in the frequent and epically intensifying boss battles, which crank the tension of combat up to eleven. Huge enemies make the player feel small and outmatched during these fights. And they’re made even more tense with the resource management of combat.

The bosses force players to methodically manage their stamina and analyze the incoming attack patterns in order to strike in between each devastating attack. All this against the overwhelming odds of some unspeakable horror.

Common Boss Organization

I postulate that most Souls-like games follow this (general) approach to presenting bosses to the player:

flowchart LR T(Tutorial) T --> 1 1[First] 1 --> A 1 --> B 1 --> C style A fill:#8b0000 style B fill:#013220 style C fill:#00008b A --> P B --> P C --> P P[Penultimate] P --> F F{{Final}}

Initially, a Tutorial boss is used to demonstrate the boss dimension of Souls-like gameplay (and how it differs from other Action-Adventure games). Players are used to dealing with enemies from earlier in their adventure, but what changes when fighting a boss?

Often, the tutorial bosses become standard enemies in the remainder of the game, like with the Rudeling from TUNIC or Sekiro’s Chained Ogre.

Then, the player continues with the game until they are confronted with their first “real” boss. This is where the game shows how difficult bosses can be.

Afterwards, the player has proven themselves worthy enough to enter any part of the world. From here, most bosses are able to be tackled in any order.

Once defeating these core bosses, and obtaining the necessary MacGuffins (e.g. in Death’s Door you need three “giant” souls; in TUNIC you need the three colored hexagons), the player will typically then present these tokens to fight the “gatekeeper” boss: a guardian of the last levels of the game, and where the player will confront the final boss.

We can see that both Death’s Door and TUNIC both follow this pattern via the boss diagrams in the appendix.

Environmental Storytelling

The mechanics of Souls-like games are also designed to create a world unwelcoming to the player. Enemies feel more powerful since players don’t have many ways to heal. Every hit taken is one fewer they’ll be able to handle as they press onwards to the next checkpoint.

Another tension emerges between the player and the world with currency that’s lost when you die. In the eponymous Dark Souls, players collect souls which can be used to upgrade character stats, but are also dropped when defeated. Upon dying, players must crawl back and re-slay enemies with the hope of reaching their cache of lost souls.

And if they die again, then their cache is lost forever. Releasing some of that tension (since players likely won’t have many souls otherwise at this point) but also creating a serious setback for the player. Imagine if you lost XP or levels upon death in an RPG. It’d make the game that much harder.

In Hollow Knight, a Shade spawns when dying, which must be defeated to recover all Geo, a valuable currency the player can use to unlock additional abilities.

Games in this genre also typically avoid exposition dumps to the player, choosing instead to encourage player exploration in the unforgiving world to find useful trinkets and the lore surrounding it in their search.

In Bloodborne, for example, the player encounters a child, desperately asking the player to recover her missing mother’s favorite brooch. This piece of jewelry can later be found on the mutilated corpse, cast aside by the area’s boss. But the most impressive twist comes when the player discovers the wife’s name engraved next to the boss’s, indicating a twisted transformation of a once loving couple.

None of this, however, is confirmed by the game, but rather an inference the player makes by connecting pieces of the environment together. Some players may choose to ignore this dimension of the game entirely, but at the very least, environmental storytelling lets players explore the game at their own pace.

A Re-expression of the Genre

We now have some basic ideas for what makes a Souls-like game. The player has less health as a resource, and must defeat unforgiving enemies with minimal damage, as resting will also heal all the enemies!

Let's look now at how these two games expand on the genre, exhibiting ways to tweak the formula as well as attempts that didn't pan out.

A Primer on Death’s Door

When also considering the developers’ previous work, Titan Souls, it’s clear the designers are heavily inspired by Souls-like games, looking to put a new spin on the genre.

|  |

|---|

Even from early in the game, it’s clear where Death’s Door gets its roots from, using the same dramatic text overlays from Dark Souls.

The Steam page description of the game is as follows:

Reaping souls of the dead and punching a clock might get monotonous but it’s honest work for a Crow. The job gets lively when your assigned soul is stolen and you must track down a desperate thief to a realm untouched by death — where creatures grow far past their expiry.

Compared to other Souls-likes, as well as TUNIC, Death’s Door is much more narratively driven, using cutscenes and a variety of memorable characters to push a stronger, first-degree storyline contrasting the slower, environmental narratives of previous entries.

A Primer on TUNIC

On the other hand, TUNIC’s narrative (as well as most of its mechanics) are rarely shown to the player. Instead, the player must figure things out for themselves via environmental puzzles sprinkled throughout the world.

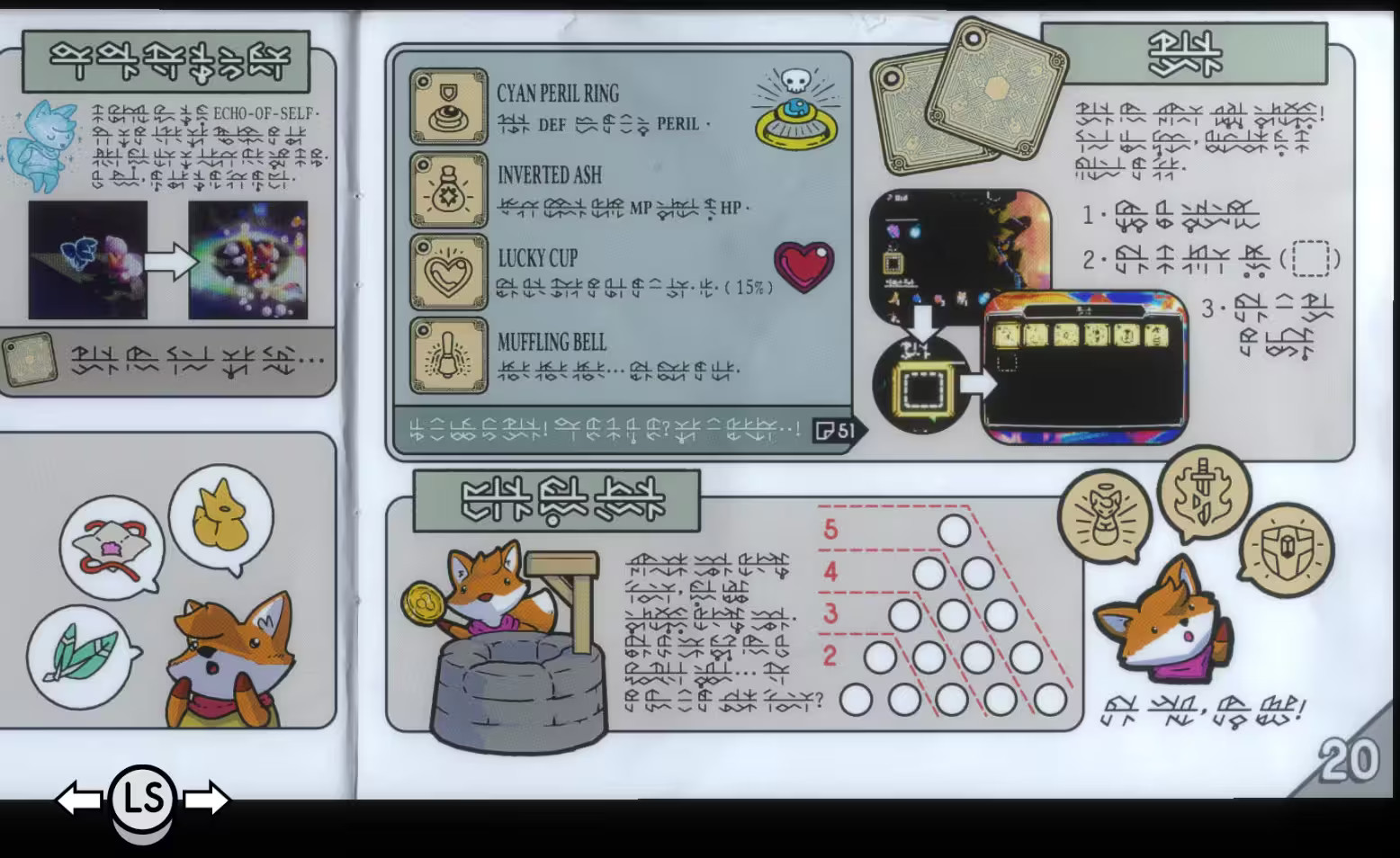

Page 20 of TUNIC’s in-game manual. Players must parse what they can out of the game’s strange and unique language.

TUNIC is described on Steam as:

Explore a land filled with lost legends, ancient powers, and ferocious monsters in TUNIC, an isometric action game about a small fox on a big adventure.

The blurb is quite vague, though given TUNIC’s more puzzle-y nature, its hard to dive deep into gameplay without giving too much away.

Let’s now examine how each game refines the genre and see how the puzzles of TUNIC meshed better with a Souls-like than the overt narrative of Death’s Door.

Different Takes on Health

As mentioned above, the healing and stamina resources are key to the Souls-like genre, creating an exciting tension between the player and an unwelcoming world.

TUNIC follows the formula, giving the player a Magic Potion highly reminiscent of Dark Souls’ Estus Flask. Players can drink from the flask to recover health, though much like attacking or dodging, the lengthy animation can leave players open for a counterattack if not planned carefully.

|  |  |

|---|

The Magic Potion (left) from TUNIC, which borrows its mechanics from Dark Souls’ Estus Flask (middle) with a touch of stylistic Zelda flair (right).

Like in Dark Souls, the flask also refills at rest points, giving players a few extra hits they can take in combat, though it can be risky if enemies are right in your face.

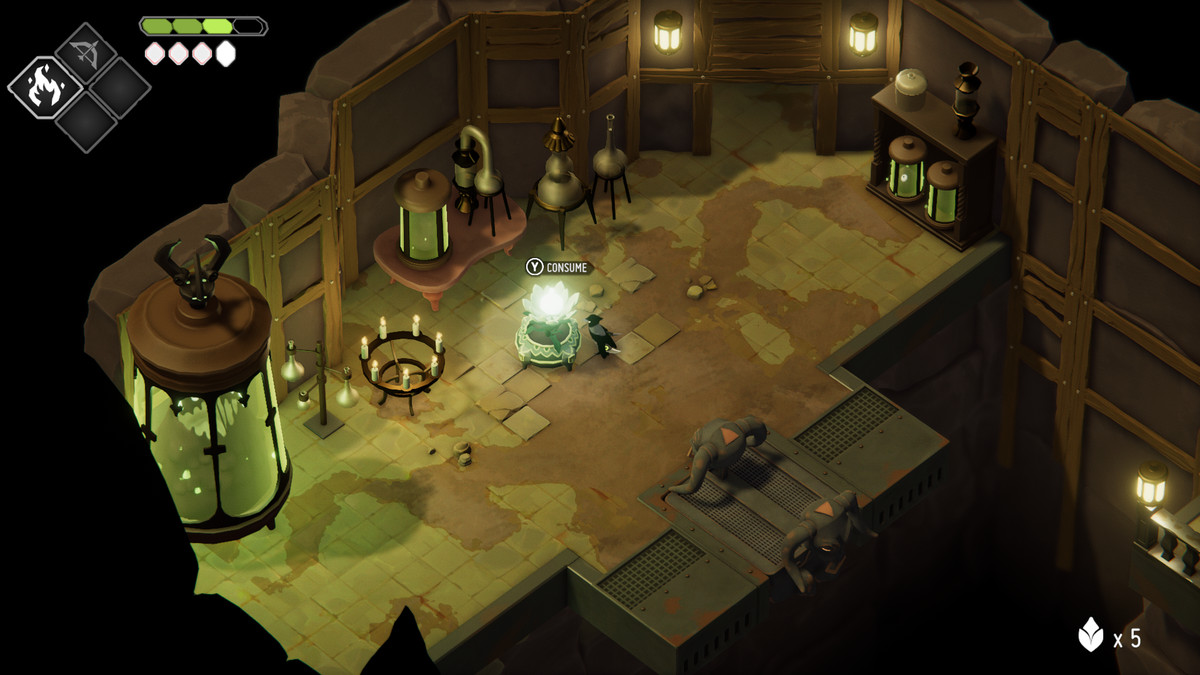

Death’s Door takes a different approach, giving players Life Seeds which can be planted in pots around the map and then consumed to heal to full health. The plants bloom again anytime the player dies, making them into more of a checkpoint mechanic.

This works well with Death's Door's old-school, pip-based health mechanic. Any hit in combat deals exactly one damage, forcing the player to be wary of simple enemies and boss attacks all the same.

A planted Life Seed in Death’s Door, ready for consumption.

The Life Seeds add some player choice to the mix; using all your seeds in one region will mean you won’t be able to heal as often in another. They also become a collectible currency, encouraging the player to seek out seeds to improve their odds.

Neither of these approaches is strictly better, though it’s refreshing to see a new take from Death’s Door, setting itself apart from other Souls-likes.

Difficulty as an Aesthetic

While Wikipedia’s definition attributes high difficulty to Souls-like games, I believe it’s defined more by the tension between the player and the world which gives a feeling of overwhelming odds while enabling the player to advance onward, despite their losses.

Let’s revisit the loss of Souls in Dark Souls. Yes, it is frustrating as a player to have your progress set back, but since enemies respawn when resting, there’s an infinite number of Souls that can be harvested.

As a result, the player will feel the pain of death, intensified further by the loss of some progress, but they can still advance. If a player wanted to, they could stay in one place, collecting Souls and then resting until leveling up so that enemies are more tenable.

I believe this gameplay loop is grindy and not the intended experience of Souls-like, but we'll see how Death's Door and TUNIC have smoothed out this approach.

Both of the games we’ve been examining cut this paradigm out; players won’t lose any resources when dying. But they’re both still able to keep the tension between the world and player in other ways.

Death’s Door, for example, doesn’t allow players to recover health within boss battles, since there are no Life Seed pots. Experienced and novice players alike will be forced to learn how to read telegraphed attacks, since there’s little room for error.

A Shrine from Death’s Door, which is one of the few ways to gain more health in the game.

Players can however, search for Shrines hidden around the world to increase the amount of hits they can take in a battle. This allows them to press on, upgrading their character without having to grind for excess Souls.

TUNIC instead chooses to builds this tension using sparse checkpoints around the map. Players will still lose progress, since, in many cases, you’ll need to defeat the same set of enemies again when making your way back into each section.

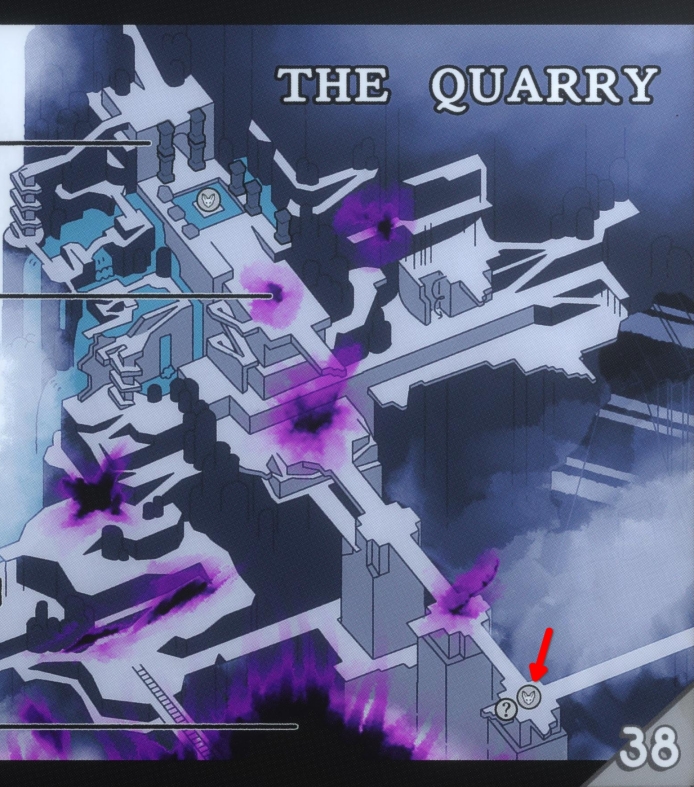

Trudging through the Quarry is especially memorable to me, since I was sent all the way back to the beginning so many times.

A map of the Quarry region, from TUNIC, which has only a single usable checkpoint location (red arrow), even for the boss!

A map of the Quarry region, from TUNIC, which has only a single usable checkpoint location (red arrow), even for the boss!

While players of TUNIC won’t be able to grind to make combat easier (since killing enemies doesn’t level you up), they can find a variety of power-ups hidden throughout the world to increase their stats.

Both games find ways to keep the feel of difficulty while still providing alternate avenues to advance. The refined design opens the genre to more casual players (especially when paired with the cute, isometric artstyle) while maintaining the core aesthetic of Souls-like gameplay.

Approach to the Narrative

Most entries in the Soulsborne series avoid explicitly explaining exposition to the player, instead choosing to embed story into the items and dungeon architecture.

Death’s Door departs from this design, using mostly cutscenes to express the narrative. Unlike most Souls-likes, though, the NPCs are whimsical and charming, making them a fun contrast against the gameplay and black-and-white overworld the player spawns from.

Above, Pothead gives a delightful introduction to The Ceramic Manor, though also dumps a fair bit of exposition onto the player, rather than letting them explore on their own.

While there are some examples of environmental storytelling using the game's collectible Shiny Things, like the Engagement Ring and Old Photograph found in the Urn Witch's Manor (perhaps a failed relationship caused her to become evil?), most items don't inspire much thought, like the Corrupted Antler or Rusty Trowel (old, discarded things, loosely related to their environment).

As a result, the characters of Death’s Door are memorable, but the story is not. It uses the typical Action-Adventure trope of “good protagonist” versus the “ruler corrupted by power”.

TUNIC, on the other hand, continues to follow the Souls-like template, leveraging environmental storytelling to weave a mystery and letting the player piece together their own interpretation throughout their journey.

The inside of the Old House, from TUNIC. The unexplained remnants of a home leave much to the imagination. The player can fill in the gaps with their own thoughts.

For example, the Old House is an important location full of a few puzzles (which I won’t spoil) and a variety of decorations to which the player gives their own meaning.

My explanation is that the protagonist of TUNIC grew up in this house before the land was overrun by monsters. This made sense to me since you can sleep in the bed and the chest is empty (because you already have what was inside?)

By coupling puzzles and narrative elements together, the “Aha!” moments are especially rewarding, since the player both solves a puzzle and uncovers more of the enigmatic forces behind the gameworld.

Although Death’s Door tries to shake up the genre by altering some of it’s core gameplay pillars, TUNIC’s faith to the formula delivers a more memorable experience. This is largely, too, due to how TUNIC innovates with new mechanics to add to the atmosphere of mystery and exploration.

Standout Mechanics

Part of what made TUNIC a more standout title is the ideas it blends with the Souls-like genre to create a new experience. To be clear, Death’s Door is still a fun, incredibly polished, isometric Souls-like. But it doesn’t quite stick with you after completion.

I had a great time playing Death's Door, but it really only came back to mind after completing TUNIC and realizing how similar the two games were.

Aside from the Life Seeds — which we’ve already discussed — Death’s Door delivers a more casual take on a Souls-like without many fresh ideas. Here are a few small remaining distinguishers:

- Players can roll without spending stamina, giving them more leeway to play defensively.

- Weapons can be upgraded via challenges to unlock powerful new effects.

- There are lots of silly achievements, like completing the game using the umbrella as your only weapon.

Both games also have a secret ending (I won't say more than that!) but TUNIC builds to it more naturally, since players are pushed to explore the puzzle-centric gameworld, compared to the narrative-focused Death's Door.

By contrast, TUNIC has three dynamite ideas which separate it from other Souls-likes, yet mesh seamlessly into the experience, though I can only talk about two of them without spoiling the game.

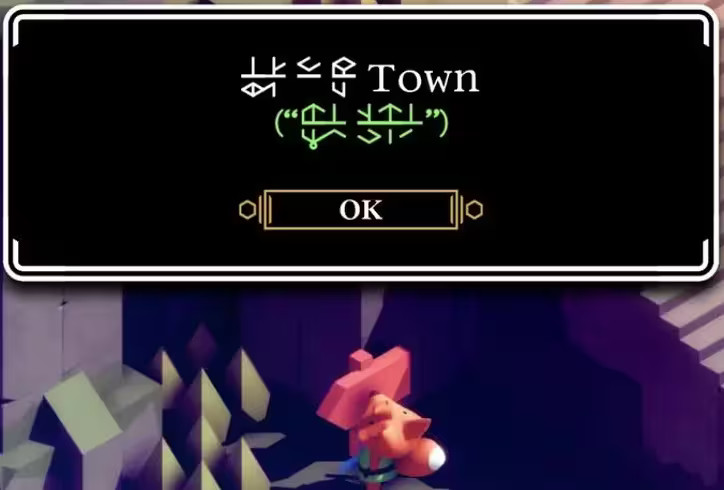

The first, most apparent differentiator is the unique language created for the game. It makes the world feel unwelcoming, as many Souls-likes do, but also mysterious and puzzling.

A sign from TUNIC in a strange and unknown language.

One of the ways I wanted to help players feel like they were in a world that wasn’t meant for them was to fill the game with a strange, unreadable language…like you were playing something you shouldn’t.

The second innovation is the in-game manual, referenced previously. It’s truly a culmination of both the core mechanics of Souls-likes and the focus on puzzle-solving unique to TUNIC.

Each page of the manual is a collectible to find within the gameworld, offering environmental storytelling (via beautiful illustrations and sparse English text), a guide for the player (like instructions for moves you could always use, but never knew how), and puzzles (which often don’t make sense initially, but reveal themselves later).

Players will pore over each manual page trying to find anything that might help them on their adventure. And these clues can often be extremely subtle, giving that “Aha!” moment, regardless of if someone is looking for an answer to a puzzle or decrypting the lore.

As for the third, perhaps this post may inspire you to play for yourself and find out! I think you'll be rewarded for your effort.

Conclusion

Design choices made by TUNIC tend to mesh better with the Souls-like genre. The puzzles pair well with the mystery and environmental storytelling, which is great way of intensifying the player’s natural desire to explore the gameworld.

Death’s Door’s heavy-handed narrative drives the game forward, but is ultimately forgettable. Despite taking larger steps away from the Souls-like genre, it fails to innovate in those areas, instead borrowing tropes from other games.

While both games are polished and enjoyable, I hold TUNIC in higher esteem and would recommend it over Death’s Door.

That being said, if you enjoyed one, you’ll likely enjoy the other! I look forward to the next entry from either studio and how they’ll refine the Souls-like formula next.

Appendix

Below are some diagrams referenced above. They are a bit too large to squeeze into a paragraph and can interrupt the reader.

Death’s Door Bosses

Below is a layout of the levels and bosses encountered within Death’s Door. It follows, to a T, the layout described above.

flowchart TD T(Grove of Spirits<br><em><strong>DEMONIC FOREST SPIRIT</strong></em>) T --> 1 1[Lost Cemetery<br><em><strong>GUARDIAN OF THE DOOR</strong></em>] 1 --> A 1 --> B 1 --> C A[Ceramic Manor<br>Inner Furnace<br><em><strong>THE URN WITCH</strong></em>] style A fill:#8b0000 B[Mushroom Dungeon<br>Flooded Fortress<br><em><strong>THE FROG KING</strong></em>] style B fill:#013220 C[Castle Lockstone<br>Old Watchtowers<br><em><strong>BETTY</strong></em>] style C fill:#00008b A --> P B --> P C --> P P[Lost Cemetery<br><em><strong>THE GREY CROW</strong></em>] P --> F F{{Hall of Doors<br><em><strong>THE LORD OF DOORS</strong></em>}}

TUNIC Bosses

The TUNIC layout is also similar, though there’s an extra set of levels squeezed in between the guardian and final boss.

flowchart TD T(East Belltower<br><em><strong>GUARD CAPTAIN</strong></em>) T --> 1 1[West Belltower<br><em><strong>GARDEN KNIGHT</strong></em>] 1 --> A 1 --> B 1 --> C A[East Forest<br>Eastern Vault<br><em><strong>SEIGE ENGINE</strong></em>] style A fill:#8b0000 B[Ruined Atoll<br>Frog's Domain<br>Grand Library<br><em><strong>THE LIBRARIAN</strong></em>] style B fill:#013220 C[Quarry<br>Monastery<br>Rooted Ziggurat<br><em><strong>BOSS OF THE SCAVENGERS</strong></em>] style C fill:#00008b A --> P B --> P C --> P P[Oubliette<br><em><strong>THE HEIR</strong></em>] P --> I I[Swamp<br>Cathedral<br>Hero's Grave] P -.-> F I --> F F{{"Oubliette<br><strong><em>THE HEIR</em> (again)</strong>"}}